We are looking for an Operations Director! Learn more and apply by March 6 for preferred application review.

Guest Blog: Air Quality Affects Birds

Tonight, hundreds of millions of birds will take flight and travel north, continuing an epic journey to their breeding grounds. They will fly in near to total darkness, reading the stars and Earth’s geomagnetic field to chart a course to their summer home. Step outside, and you may hear them calling overhead, or catch sight of their silhouettes against the moon.

Birds need clean air.

For me and so many other birders, the arrival of spring migrants is truly a celebratory occasion, one that inspires wonder and gratitude and marks the passing of time. There is something profound – both joyful and reassuring – in the return of our feathered friends. Even as our human lives are fraught with war and famine, protest and heartache, illness and loss, birds press on. In an uncertain and perilous world, birds are one of the few things we can count on to ground us.

And now, more than ever, birds are counting on us. Birds are on the decline globally, threatened by climate change, habitat loss, invasive species, overexploitation, and human-wildlife conflict.

Olivia Sanderfoot is a postdoc at UCLA studying how air quality affects birds. In December 2022, she shared a fast-paced, five-minute, 20-slide, Ignite@AGU talk, held under the stars at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, Illinois.

Air pollution is also a known risk to birds. For more than a century, birds have served as sentinel species for environmental contaminants. Caged canaries warned miners of dangerous levels of toxic gasses, and the sudden decline of raptor populations foreshadowed the dangers of DDT.

Yet, few studies have explicitly linked air pollution to the distribution and abundance of birds. This gap limits our ability to predict how worsening pollution with global change will affect bird populations. To develop effective policies to avert further declines, we must address this knowledge gap, and soon.

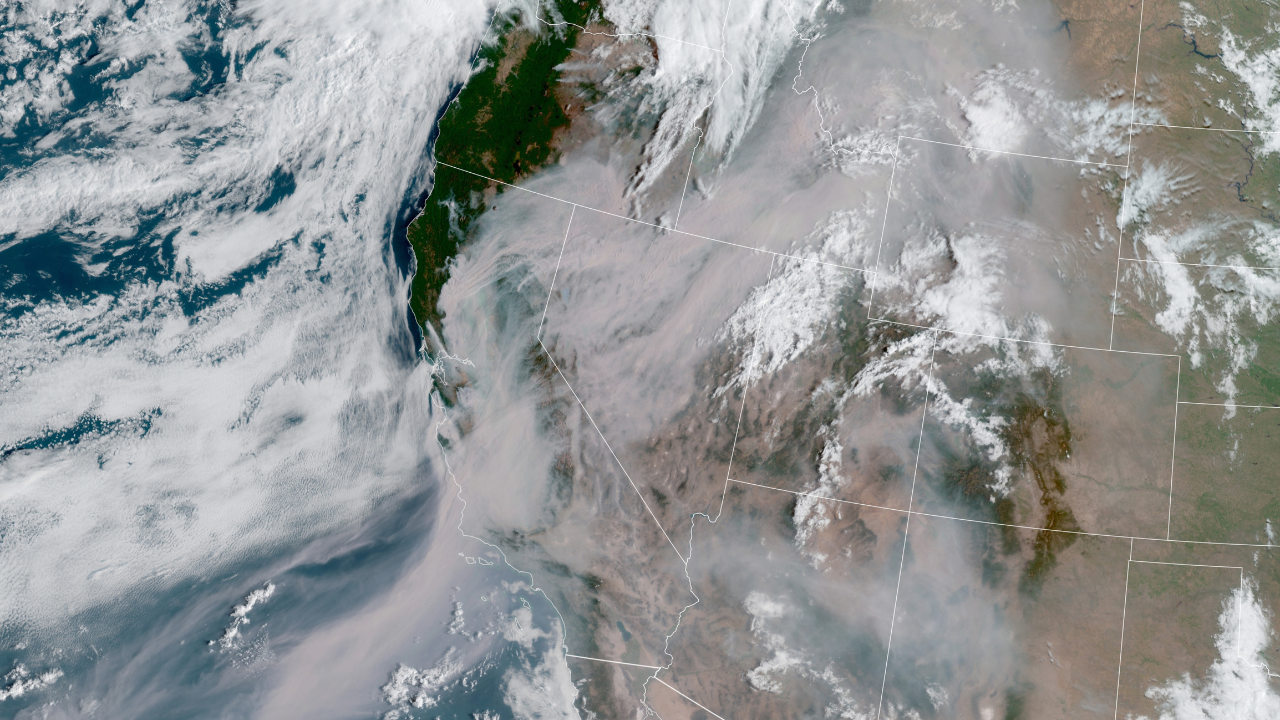

Smoke Affects Birds

A Northern Shoveler swims while surrounded by smoke from the Cedar Creek fire. Credit: Sevilla Rhoads

Birds of a Feather

Olivia Sanderfoot studies how pollution and air quality affects birds. Credit: Olivia Sanderfoot

Precarious Balance

Birds are in decline across North America, with many populations precariously balanced, much like this Fork-tailed Flycatcher. Credit: Graham Montgomery

Humans and Birds

Many birds have adapted to living with humans. But new research is revealing how much air pollution affects them. Credit: Clay-colored Sparrow – Graham Montgomery

Take Flight

In order to fly, birds depend on a highly efficient respiratory system, which also makes them sensitive to air pollution. Credit: Redheads – Graham Montgomery

Air Pollution Impacts

A red-tailed hawk sits on a burned tree during the Cedar Creek fire. Credit: Sevilla Rhoads

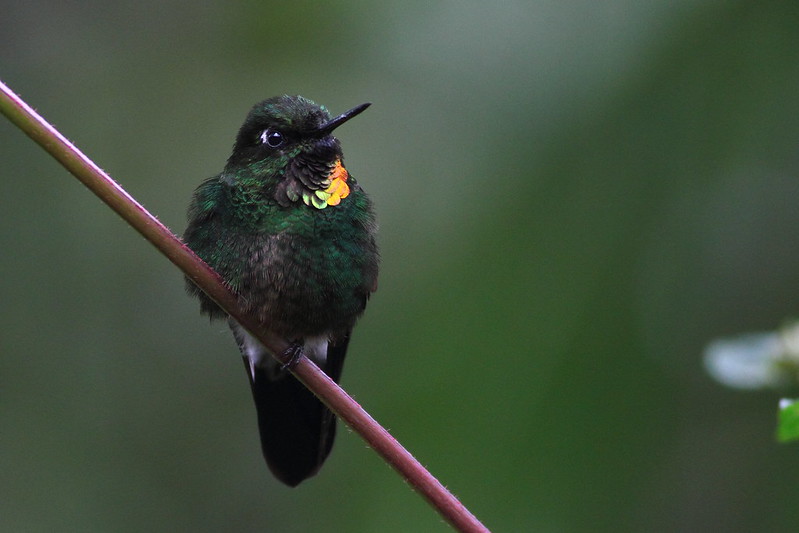

Feathered Friends

“‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers.” – Emily Dickinson Credit: Flame-throated Sunangel – Graham Montgomery

Air quality affects birds – but how?

I believe that interdisciplinary collaboration within the Earth sciences is the key to advancing knowledge of air pollution impacts on birds.

In 2017, I led the first systematic literature review on the effects of inhalation exposure to air pollution in birds. We identified significant limitations in our understanding of how airborne toxins affect birds, most notably a lack of robust exposure estimates.

For one, air pollution is rarely measured directly. Instead, many researchers make comparisons between urban and rural locations, or consider how effects vary with distance from an emissions source, such as a power plant. However, these approaches rely on the assumption that the air we breathe is always cleaner in less densely populated areas, or farther from industrial sites. This is not always true – weather, geography and other factors also influence local air quality conditions. For example, during the devastating fire season of 2020, toxic smoke blanketed the American West, affecting rural, suburban and urban areas across hundreds of miles.

Furthermore, it is not enough to know that air pollution is better or worse – we need to know how birds are impacted as the intensity of air pollution changes. How do the effects of air pollution on birds change as concentrations increase or decrease? Do risks scale linearly? How does the duration of exposure – such as the number of days communities are impacted by wildfire smoke – influence the effects of air pollution on birds?

Without explicitly measuring air pollution, we cannot characterize how birds are affected by air pollution across a wide range of air quality scenarios. And we cannot determine if there are “safe” levels of air pollution below which birds experience minimal impacts. We need this information to develop effective conservation policies to protect birds.

In our review, we proposed that by leveraging tools from the atmospheric sciences community, including ground-based monitors, air quality models, and satellite instruments, ecologists could better quantify avian exposure to air pollution.

Through interdisciplinary collaboration, I study how air quality affects birds.

As a doctoral researcher, I strived to do just that. I led integrations of community science data with measurements from sensors and output from chemical transport models. Specifically, I explored how particulate matter influences how likely we are to observe birds.

As a postdoc, I apply these same approaches to study how wildfire smoke influences avian behavior, ultimately shaping soundscapes and species distributions. Collaborating with researchers in ecology and atmospheric science has strengthened my belief that while disciplinary divides may have limited research to date, intentional partnerships across branches of science can transform our understanding of environmental stressors on wildlife. Ecologists and atmospheric scientists may not solve problems in the same way – we may even differ on our preferred coding language or file type – but by working together, we can develop innovative approaches to novel questions.

Earth scientists can collaborate to link air pollution and birds

Recent examples of interdisciplinary collaborations to study impacts of air pollution on birds are incredibly promising, and demonstrate the value of clean air for people and wildlife.

In 2020, researchers linked observations from eBird, a global community science program, with data from the EPA’s Air Quality System to explore how air pollution influenced population trends over four decades. They showed that the same air quality regulations designed to limit ozone to protect human health also mitigated the loss of 1.5 billion birds in the U.S.

While air pollution in the U.S. has largely improved in recent decades, thanks to increasingly stringent environmental regulations and technological advancements, smoke from wildfires is erasing this progress, and it is unclear how birds will be impacted. In 2021, researchers linked GPS locations of geese to output from NOAA’s High Resolution Rapid-Refresh model to examine how migrating birds responded in real-time to wildfire smoke. They found that birds flew off course, attempted to fly above the smoke or paused their journey altogether, suggesting that smoke from megafires may be hugely disruptive to bird populations.

ESIP brings together collaborators

ESIP supports virtual and in-person collaborations for cross-domain data professionals on common data challenges and opportunities. Alongside our partner organizations, we create space for Earth science data professionals to connect.

Learn more and join an ESIP Collaboration Area: esipfed.org/collaborate

With spring migration in full swing, there is no better time to think about how Earth scientists can work collectively to safeguard birds. If you are a birder, community leader, atmospheric scientist, data manager or fellow ecologist keen on this idea, let’s connect this spring. You can reach me by sending an email to osanderfoot@ucla.edu… or maybe I’ll meet you out birding.

Interested in continuing the conversation? Reach out to Olivia directly and join the ESIP Air Quality Cluster and our other Collaboration Areas to make interdisciplinary, data-driven #EarthScience projects happen between federal agencies, industry, and academia.

This blog was written by Olivia Sanderfoot, with edits from Allison Mills and Annie Burgess. The video was filmed in December 2022 during the Ignite@AGU event at the Adler Planetarium.

The images are from Graham Montgomery (grahammontgomery.us), Sevilla Rhoads, and Olivia Sanderfoot as noted in the captions. We appreciate their generosity to share within this blog. Please request permission directly from the photographer before using or sharing their images.

ESIP stands for Earth Science Information Partners, a community of partner organizations and volunteers. We work together to meet environmental data challenges and look for opportunities to expand, improve, and innovate across Earth science disciplines.

Learn more esipfed.org/get-involved and sign up for the weekly ESIP Update for #EarthScienceData events, funding, webinars and ESIP announcements.